Why Your Child Remembers Every Pokémon But Can’t Remember to Brush Their Teeth

Why Your Child Remembers Every Pokémon But Can’t Remember to Brush Their Teeth

The ADHD Memory Paradox That Confuses Every Parent — And What It Really Means

Here’s the scene I witness almost weekly in my consulting room.

A mother sits across from me, exhausted and bewildered. Her nine-year-old son has just rattled off the evolutionary chain of every starter Pokémon from generations one through eight — including their types, weaknesses, and optimal movesets. She turns to me with that particular look I’ve come to recognise: half-impressed, half-despairing.

“He can remember all of that,” she says, “but this morning he forgot to put on socks. Again. And yesterday he couldn’t remember to bring his homework home — the homework he’d spent two hours completing.”

I nodded. After twenty years of working with ADHD children and their families, I’ve heard variations of this conversation thousands of times. Your child’s grandmother’s phone number? Memorised at age five. The capitals of every country? Flawless recall. But brushing teeth, putting shoes by the door, handing in completed work? It’s as if the information evaporates the moment you stop speaking.

This isn’t laziness. This isn’t defiance. This isn’t your child choosing to forget the boring stuff. This is the ADHD memory paradox — and once you understand it, everything about your child’s behaviour starts making a different kind of sense.

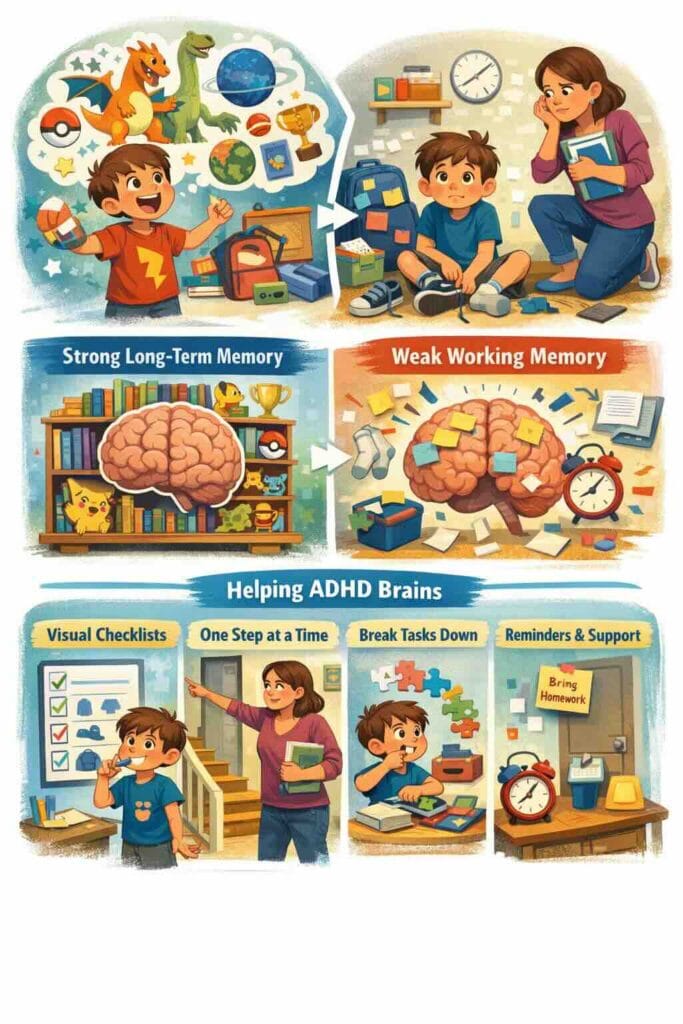

Two Memory Systems, Two Different Stories

Let me explain something that transforms how parents understand their ADHD children. Your brain doesn’t have one memory — it has several distinct memory systems, each serving different purposes and operating through different neural pathways.

📚 Long-Term Memory

Your brain’s vast library — the storehouse of facts, experiences, skills, and knowledge accumulated over your lifetime. This is where Pokémon evolutionary chains live, alongside your childhood memories, how to ride a bicycle, and the lyrics to songs you haven’t heard in decades. Capacity: Essentially unlimited. Duration: Minutes to a lifetime.

📝 Working Memory

More like a mental sticky note — a temporary workspace where your brain juggles information it needs right now to complete the task at hand. It holds perhaps three to five “chunks” of information for a few seconds to a few minutes while you actively use them.

Here’s the crucial point that changes everything: ADHD significantly impairs working memory while often leaving long-term memory relatively intact. Research published in the journal Clinical Psychology indicates that working memory deficits are present in approximately 75 to 81 percent of children with ADHD — with these impairments showing very large magnitude effects in studies.

This isn’t a subtle difference. This is the neurological reality behind your child’s seemingly contradictory memory performance.

What Exactly Is Working Memory Doing?

Think of working memory as your brain’s mental workbench — the space where information is temporarily held, manipulated, and used to guide behaviour in the moment. Unlike passive storage, working memory is active. It’s not just holding information; it’s doing something with that information while simultaneously screening out distractions.

Let me give you a practical example. Imagine you’re doing mental arithmetic: calculating 24 multiplied by 18 in your head. Your working memory must simultaneously hold the numbers 24 and 18, perform intermediate calculations (4 times 8 equals 32, 20 times 18 equals 360), maintain awareness of which step you’re on, ignore the television playing in the background, and finally combine partial results to reach 392.

Now imagine trying to do that calculation while someone keeps changing the numbers. Or while the results of your intermediate steps keep slipping away before you can use them. Or while your attention keeps drifting to that fascinating bird outside the window.

That’s what learning — and life — often feels like for children with ADHD.

The Daily Disasters Working Memory Creates

Working memory touches almost every aspect of daily functioning. It’s not just about school or homework — though it certainly affects those. It’s about navigating life itself.

Following Instructions

You tell your child: “Go upstairs, brush your teeth, put your school uniform on, and bring down your library book.” By the time they reach the top of the stairs, the instruction is already fragmenting. They brush teeth (maybe), see their Lego creation, spend ten minutes adjusting it, and return downstairs in pyjamas asking what they were supposed to be doing.

This isn’t defiance. The instruction genuinely couldn’t stay active in their mind once something more interesting appeared. The mental sticky note fell off the fridge.

The Homework Catastrophe

Your child sits down to write an essay. Working memory must simultaneously hold the essay question in mind, formulate thoughts, remember spelling and grammar rules, maintain awareness of paragraph structure, recall relevant facts from lessons, and physically form letters while keeping their pencil moving in the right direction.

For a child with ADHD, this is like trying to juggle seven balls while someone periodically shouts distracting comments and occasionally steals one of the balls. Possible? Sometimes. Exhausting? Always. Sustainable? Rarely.

Social Struggles

Working memory affects social interactions too. Your child interrupts constantly — not from rudeness, but because they can’t hold their thought in working memory long enough to wait for a gap in conversation. If they don’t say it now, it’s gone forever.

They forget playdates, forget to respond to messages, forget what they agreed to do. Other children don’t understand these are neurological difficulties. They just know your child is “unreliable” or “doesn’t listen.” And slowly, friendships suffer.

Learning and Comprehension

Here’s something crucial: if a child can’t hold a thought still long enough to process it, they can’t encode it into long-term memory. Focus is the gateway to learning. Without that split-second of sustained attention, information never makes it from the mental workspace into permanent storage. The thought blows away before it can be packed down.

Solving the Great Paradox: Why Pokémon Sticks

So how can your child remember 800 Pokémon but not three morning tasks? This isn’t mysterious once you understand how these memory systems differ.

🎮 Pokémon Knowledge Was Acquired Through Repeated Exposure

Over weeks, months, years. Each encounter reinforced neural pathways. Your child watched episodes, played games, discussed with friends, imagined battles. The information was processed during high-engagement, high-dopamine states when their attention was naturally captivated. Most importantly, it was encoded into long-term storage through multiple channels over extended time.

☀️ Morning Instructions Require Working Memory

The temporary holding and manipulation of information to guide immediate behaviour. The instruction must remain active in the mental workspace while competing with every distraction: the fascinating crack in the ceiling, yesterday’s unfinished thought about dinosaurs, the suddenly urgent question about what’s for dinner.

Research confirms this distinction. Studies show that ADHD doesn’t directly impair long-term memory storage — instead, it affects the encoding process, the ability to move information from working memory into long-term storage. When encoding happens naturally through high-interest, repeated exposure, information gets through. When it requires sustained, deliberate attention to boring material, the system struggles.

This is why your child isn’t being selectively forgetful to annoy you. Their brain literally processes interesting and uninteresting information through different pathways — and ADHD affects one pathway far more than the other.

The Neuroscience: What’s Actually Happening

Understanding the brain mechanisms helps parents move from frustration to compassion — and from compassion to effective support.

Brain imaging consistently shows that children with ADHD have lower activity in the prefrontal cortex — the brain region responsible for attention, planning, and memory encoding. There’s also underactivity in dopamine pathways, the chemical messengers that help us feel reward, motivation, and sustained interest.

This means ADHD brains get bored more easily, need more stimulation to stay engaged, and struggle to filter out distractions. A chair scraping across the floor, a bird outside the window, a passing thought about lunch — each of these can derail the working memory process, causing the original information to slip away.

Neuropsychological research reveals something important: the working memory deficit in ADHD involves what scientists call the “central executive” — the control system that manages and manipulates information. This isn’t just passive storage failing; it’s active management breaking down.

Think of it like an orchestra without a conductor. All the instruments (memory components) are present and capable. But without someone coordinating them, maintaining focus, and keeping everything working together, the result is chaos rather than symphony.

Understanding the Memory Landscape

It helps to understand the different memory types and how ADHD affects each:

👁️ Sensory Memory

Captures immediate sensory information for less than a second — the trailing image of a sparkler, the brief echo of a sound. Largely unaffected by ADHD.

📱 Short-Term Memory

Holds small amounts of information passively for 15-30 seconds — like a phone number just long enough to dial it. Research suggests visuospatial short-term memory (remembering visual patterns) may be more affected in ADHD than phonological short-term memory (briefly holding verbal information).

⚙️ Working Memory

Actively manipulates and manages information for immediate tasks. This is the major deficit in ADHD, affecting three-quarters or more of children with the condition.

🏛️ Long-Term Memory

Stores information relatively permanently with unlimited capacity. Includes episodic memory (personal experiences), semantic memory (general knowledge), procedural memory (skills), and prospective memory (future intentions). Long-term storage may be relatively intact — but getting information into storage requires successful encoding, which depends on attention and working memory.

📅 Prospective Memory

Remembering to do something in the future — particularly problematic because it requires working memory to hold the intention while also doing other things. “Remember to bring your PE kit tomorrow” demands exactly the kind of sustained, deferred attention that ADHD brains struggle with most.

Real-World Impact: A Day in the Life

Let me walk you through what working memory difficulties actually look like across a typical school day:

Your child goes upstairs to get dressed. Working memory holds the instruction: get dressed. They walk into their room and see yesterday’s drawing. Working memory drops the original instruction; attention shifts to the drawing. Five minutes examining what they made. You call upstairs. They’re startled — were they supposed to be doing something?

Teacher gives instructions: “Open your workbooks to page 47, read the passage, and answer questions 1-3.” By the time your child finds page 47, they’ve forgotten the rest. They stare at the page, aware they should be doing something but genuinely unsure what.

Friend asks: “What did Mrs. Johnson say about the project?” Your child heard the explanation twenty minutes ago but couldn’t hold it in working memory long enough to encode it. They feel stupid. They make something up to save face.

Packing up for home. Your child remembers homework exists but can’t recall what specifically was assigned. They grab what they think they need. The actual homework sheet is still in their desk.

Homework time. Your child sits down to complete the worksheet. They read the first question. Start formulating an answer. Notice a scratch on the table. Examine it. Wonder how it got there. Suddenly realise five minutes have passed. What was the question again?

Each moment isn’t deliberate failure. It’s working memory — that crucial mental workspace — repeatedly losing its contents before tasks can be completed.

What Actually Helps: Strategies That Work

Understanding that this is a working memory issue rather than a character flaw immediately suggests practical solutions. The goal isn’t to “fix” working memory through sheer willpower — it’s to reduce demands on an overloaded system while providing external support.

📋 Externalise Memory

Since internal memory is unreliable, create external memory systems. Checklists stuck to the bathroom mirror. Visual schedules with pictures for each step. Laminated routine cards that your child physically checks off. The information lives outside their head, where it can’t slip away.

Try this: A morning checklist including every single step: wake up, take medication, shower, get dressed, eat breakfast, brush teeth, pack bag, put on shoes, collect lunch from fridge. Laminate it. Use dry-erase markers to check off. Reset daily.

🎯 Reduce Cognitive Load

Give one instruction at a time. Not “Go upstairs, brush teeth, get dressed, bring your bag” — just “Go brush your teeth.” When that’s done, give the next instruction. Yes, it’s slower. Yes, it requires more of your time. But it actually works, which the alternative doesn’t.

Break large tasks into tiny, manageable chunks. Not “Do your homework” but “Read the first question and write the first sentence of your answer.” Then acknowledge completion before moving to the next tiny step.

📍 Use Strategic Placement

Put things where they can’t be missed. PE kit in front of the door on PE days. Library book on the breakfast table when due back. Permission form literally inside a shoe — they cannot leave without encountering it. If they can’t miss it, they won’t forget it.

📱 Leverage Technology

Modern smartphones are external brains. Set recurring reminders: take medication (daily, 7am), pack PE kit (every Monday, Sunday evening), check planner (daily, after school). Reminders should be specific — not “homework” but “Submit English essay to teacher.”

🔄 Teach Rehearsal Techniques

For important things that must be remembered, use physical rehearsal. “Tomorrow you need to bring your permission form. Let’s practice.” Actually walk through the sequence: get the form, put it in bag, put bag by door. Mental and physical rehearsal together create stronger memory traces than verbal reminders alone.

💊 Consider the Role of Treatment

When appropriately prescribed and monitored, ADHD medication can be transformative for working memory — not because it changes your child’s personality, but because it helps increase the “stickiness” of that mental workspace. It gives the brain the neurochemical support it needs to hold information just that crucial bit longer. Medication doesn’t fix working memory directly, but it reduces distractibility and increases focus, which makes it easier for children to access and use their working memory.

What This Understanding Changes

When you truly grasp the working memory component of ADHD, your interpretation of your child’s behaviour transforms.

This isn’t making excuses. Your child still needs to learn to function in a world that demands follow-through and organisation. But understanding the neurology beneath the behaviour helps you provide effective support rather than ineffective criticism.

It also protects your relationship. When you see forgetfulness as “won’t” rather than “can’t,” you react with frustration and punishment. When you understand it as a neurological difficulty, you react with support and scaffolding. The child learns the same skills either way — but one approach preserves their confidence and your connection, while the other erodes both.

There Is Hope Here

I want to end where I always try to end with parents: with hope grounded in understanding.

Working memory difficulties are real and challenging. They create daily friction, academic struggles, and social complications. But they’re also manageable with the right support.

External systems compensate for internal limitations. Strategies become habits. Technology provides scaffolding. And as the brain matures — because it continues developing into the mid-twenties — executive functions including working memory gradually strengthen.

Your child isn’t broken. They’re working with a brain that processes information differently — one that needs more external structure, more frequent check-ins, more visual reminders, and more patient repetition. With understanding and support, they can absolutely thrive.

That child who remembers every Pokémon? That same remarkable memory capacity exists within them. The challenge is creating the conditions — through environment, support, and sometimes treatment — where that capacity can be harnessed for the tasks that matter.

“Understanding is the most powerful intervention we have. When parents truly understand their child’s brain, they stop fighting against neurology and start working with it. And that changes everything.”

Ready to Understand Your Child’s Unique Brain Better?

Dr John Flett offers comprehensive ADHD assessments and family support at The Assessment Centre in Kloof, Durban.

Serving families across South Africa

Responses